The one thing we don't talk about when we talk about trauma

Something interesting happened over the past few years: everyone found therapy.

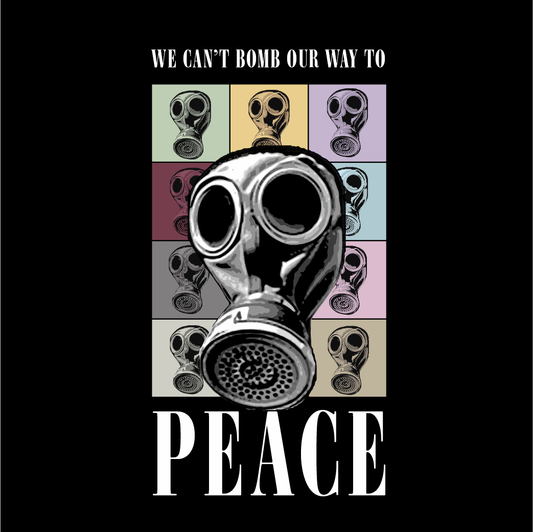

On balance, this is hugely positive. If we want more peace, inside and out, our understanding of mental health is key. But as with any new (or new-to-me) technology, misuse is rampant.

Here are three things to watch out for as we embrace a more integrated understanding of well-being that goes beyond our bodies.

Mental Health as a Weapon

A growing number of n00bs now think they’re qualified to diagnose the mental health of others.

Stop me if you’ve heard this one: someone says something that causes a strong divergence of opinions. Soon, a mental health diagnosis is being applied to what was historically known as a disagreement. Technical and explosive terms like “narcissist”, “gaslighting”, and the assignment of “therapy” are lobbed around with little care for their impact on, ironically, mental health.

So if your growing awareness of complex human struggles leads you to curiosity, empathy, and patience, you’re probably doing it right.

But if it leads you to play doctor and dole out diagnoses and treatments from on high, maybe it’s time to look into your own possible delusions of grandeur.

Mental Health as a Shield

If the weaponization of “mental health culture” is the most obvious problem, the duck-and-cover problem might be the most confusing and insidious.

The acceleration of online division, along with the rise in mental health awareness, has led to the co-opting of mental health for public relations purposes. Take the iPhone-Notes-app or YouTube Apology: a sorry, often with vague references to “stuff I’ve been going through”, “having a breakdown”, or “taking some time away for my mental health”. In many cases, these apologies feel as though they come too quickly for real introspection. The invocation of anxiety, past trauma, etc seem like running to “base” on the playground to avoid being tagged.

And hiding behind mental health isn’t the domain of celebrities alone. Institutions deploy the tactic, too.

I met an executive who was pressured into a $15,000 luxury therapy retreat, told it’d help the company amidst an HR dust-up to claim they were suffering from PTSD. They protested because they were already in therapy. Their therapist refuted the armchair PTSD diagnosis and said a mandatory retreat was more likely to disrupt their mental health.

The ploy was not evil. The powers above them no doubt meant it for good. Still, the cultural ease with which a “trauma” was invented and used to shield everyone else was ethically and legally dubious.

The Dilution of Meaning in ‘Mental Health’

Most people want to be seen as unique. Yet we see the same terms that uniquely describe our plight (anxiety, trauma) being applied to all manner of everyday experience.

As everything inches closer to “trauma”, how is any mental health language meaningful? If everything is “toxic” and everyone who rejects my premise is “gaslighting” me, maybe the problem isn’t what we think it is. Maybe it’s collective hypochondria.

What if we’ve taken the hammer of “psychology” and we’re just haplessly whacking every suboptimal experience, claiming it’s a nail? What if it’s all a big Rorschach test and the names we project onto the inkblots of everyday life say more about us than anything?

A final word: not all therapy is created equal

“You need therapy” and “get help” are typical online barbs. But one thing is clear: not all therapy is created equal.

Systemic and historical acknowledgements all equal, the methodologies that focus on “how you feel about what they did to you” seem to produce entrenched victimhood. While those that focus on “what you’re going to do about yourself moving forward” tend to give rise to empowered builders of change.

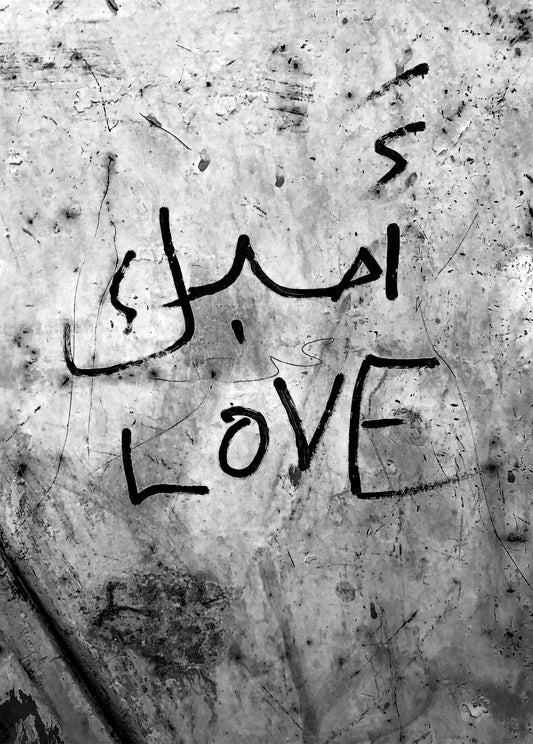

My therapist says, “Your job is to keep your side of the street clean.” If someone wants to live in filth, that’s their business. There’s nothing I can do about other people. What I need to do is make myself better. And better. And better. And the more I stay focused on “my side of the street”, the less time or inclination I have to worry about anyone else’s trash.

Often, I come to realize that their side of the street wasn’t that dirty anyway. It was me. My heart. And my way of seeing things.